Bereave wants employers to suck a little less at navigating death

If death and taxes are inevitable, why are companies so prepared for taxes, but not for death?

“I lost both of my parents in college, and it didn’t initially spark this interest to go start a business around my experience,” said Bereave co-founder Elijah Linder.

In the immediate aftermath of Linder’s loss, founding a company would have been a long shot. But in 2020, when co-founder Matt Tyner’s mother died, the two of them got the idea to build something that could have made their experiences even marginally less awful.

“I had the entrepreneur bug – I just waited until I saw a problem and a mission worth going after,” Linder said.

Along with CEO Justin Clifford, the Indianapolis-based team conducted a series of interviews with people experiencing loss to get a better idea of where they could make the most impact.

“In these conversations, people would say, ‘Here’s who we lost, here’s when we lost them.’ And then they would say, ‘Here’s how my manager reacted,’” Clifford told TechCrunch. “And it was like, ‘Wait a minute, why are you talking about your manager right now?’”

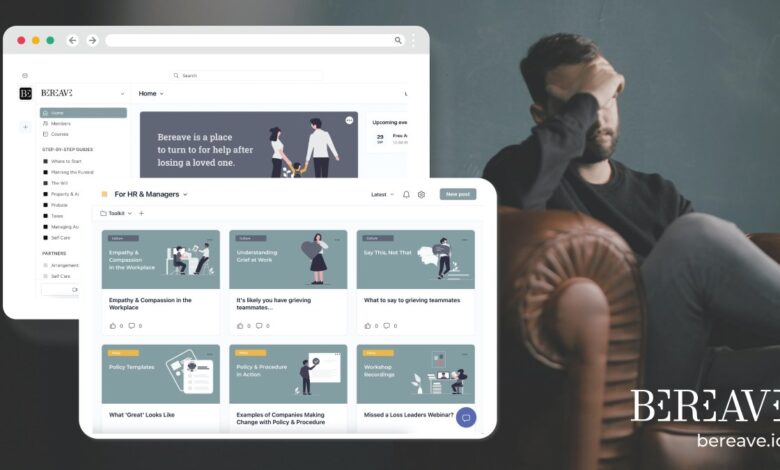

It became clear to Bereave that people were struggling to navigate grief in the workplace. So Bereave built a B2B product to sell to employers, which they can offer their employees in times of need. The platform catalogs resources for people experiencing loss, walking them through the steps of closing out a loved one’s affairs. So far, the company has about 12 clients who pay an annual fee based on how many employees they have – a company with 100 employees would pay $1,000 per year, whereas a company with 1,000 employees would pay $5,500.

“Most death tech companies that are going into B2B are very niche – like, they’re counseling, or they’re maybe focusing on one or two pieces of the puzzle,” Clifford said. “What we’re trying to do is bring everything together to make sure that there is one source for the businesses.”

The mental toll of grief can be compounded by the overwhelming list of tasks to do when someone dies – the living relatives of the deceased have to navigate taxes, insurance cancellations, credit card and bank account transfers, wills, and more.

“The whole idea is, you don’t necessarily have to think,” Clifford said. “You’ve got a whole checklist in front of you.”

In a crisis, these sorts of checklists are invaluable, which is why this model exists in other HR products. Tall Poppy, a company that offers digital safety guidance for employees navigating online harassment and hacks, also uses step-by-step checklists.

Beyond providing a few days of time off for bereavement, and maybe some counseling sessions, employers don’t often have much support in this area. So, on the employer side, Bereave offers resources that outline how to support an employee through a loss, or what to do if an employee passes away. These resources are also helpful for team members, including modules that explain how to sensitively talk about loss, or even what kinds of food to provide a grieving family.

“You’re planning for everything else in the business. What happens if somebody goes on maternity leave, or some other sort of FMLA?” Clifford said. “There are things that happen that are planned, and this is just not one of them.”

The decision to build software to sell to employers is clever. HR departments are more likely to seek out and pay for these sorts of resources than individual people, and as Bereave’s founders learned in their research, the funeral industry is a bit slow to adapt to offerings like this. But it’ll take time before Bereave can grow into the service it aspires to be.

“We’re in the midst of a fundraise right now to be able to take that cobbled together system and turn it into enterprise-grade software, and really be able to talk about automation for HR folks and managers,” Clifford said. “So when these things happen, HR, teammates and managers can just execute. They don’t have to think about what to do.”

Source link